Vol.5

ConversationJanuary 11, 2013 UP

“Theater and the City”

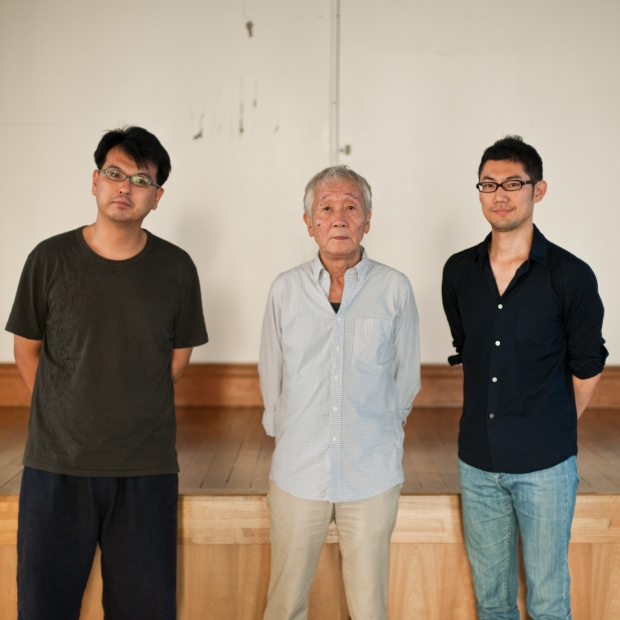

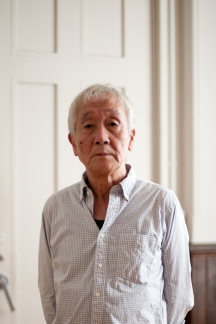

Yukichi Matsumoto, Motoi Miura & Yusuke Hashimoto

- interlocutor1:Yukichi Matsumoto

- interlocutor2:Motoi Miura

- MC:Yusuke Hashimoto

- Photo:OMOTE Nobutada

- text:Masako Tago (KYOTO EXPERIMENT)

Post-modern theater has always synchronized with the emergence of the city. What is the “city” we can see in theater? And what does theater mean to a city? With these questions in mind, Yusuke Hashimoto, the program director for KYOTO EXPERIMENT performing arts festival, interviewed the internationally renowned theater directors, Osaka-based Yukichi Matsumoto (director and set designer for Ishinha) and Kyoto-based Motoi Miura (director for Chiten).

Approaches to a Multi-Layered City

Hashimoto: To start, I’d like to consider both your theater work. A bird’s eye view of Japan shows that Tokyo dominates as the center, surrounded by regional cities. And yet both of you have made conscious choices to be located in cities that are not the “center” as bases for your theatrical activities. Additionally, Yuichi’s company, Ishinha, always creates large-scale outdoor sets and so-called yataimura, “food stalls villages.” We could call this special space a fictional one, connected to the theater world, but one that seems to erode away into an actual town. Not only the content of your work but also your method of organizing theater provides many perspectives for thinking about the city, and so I asked you to participate in this talk today.

Your latest production, “Yugao no hanashiroki yugure” (2012) (Design and Creative Center Kobe), has the subtitle, “Perspective play for City” [sic]. I was really fascinated by the play, especially the stage set, which was electrifying in its use of concrete stage effects like illusions, created by perspective. But not only that, the word “perspective” itself has the sense of the world seen from the point that establishes the modern city. Can you share your understanding of perspective in relation to the city?

Ishinha, “Yugao no hanashiroki yugure” (2012) (Design and Creative Center Kobe) photo by:Yoshikazu Inoue

Ishinha, “Yugao no hanashiroki yugure” (2012) (Design and Creative Center Kobe) photo by:Yoshikazu InoueMatsumoto: Ishinha has staged a trilogy on what we might call urban theory, or the city. I was in my late thirties when I started it and have continued the series until today. Our themes include urban observation, the city of the future, the birth of the city, and a kind of history of the city. We have taken many different approaches, but what I have come to realize at my age is that my perspective on the city has clearly changed. All I can say now is that a city is multi-layered, that it is complex. One example is geography. Take Osaka, at the very bottom there is a layer containing the fossils of prehistoric elephants. On top of that, there is the Jomon era, and then the medieval period, followed by the modern era, which includes the so-called period of scientific progress and also rubble from the war. It really is stratified. And what I feel strongly here is the existence of foreigners. Not only Koreans, but there are also lots of Chinese, Brazilians, and people from Okinawa. This ethnic influx is not built up like easy-to-understand blocks, but each layer forms curves. It is complex. If I was to be asked what my sense of the city is – which layer of the city I myself am in – I would not be able to describe this in one word. It is about from which layer I find my own place, connecting this to a dramatization of the city and making theater in the city. Depending on the times, the approach is different and the way of doing it changes. Searching for your own place or confirming the uncertainty of your place... And it is a sense of reality that is Osaka and the city. I have engaged with urban theory for a long time in Osaka, and now I think that at the core I intentionally involve myself physically in that theme

Hashimoto: How have audiences reacted? I heard a lot of praise, especially for the stylized parts.

Matsumoto: Yes, I worked in a stylized or formalistic way since for some reason I wanted to lyrically create a lyrical idea that was inside me. The audiences seemed to really understand what I was doing. In the productions, the actors did not perform like in a rigid play, but more loosely. I feel that that kind of interlocking is one method for cutting into the city. But not just this, from now I want to try out many new things as well.

The “Modern” Sensed from Japanese Modern Literature Writers

Hashimoto: Now I would like to turn to Motoi Miura. I think what is critical here is that not just yourself but all the members of your company have relocated to Kyoto. In your stagings for the “NIPPON Bungaku Series” (Japanese Literature Series)(*1) at the Kanagawa Arts Theatre (KAAT) and “CHITEN no kingendai-go” (Chiten’s Modern-Contemporary Language) (2011, premiere at Toshima Kokaido Hall, Tokyo), I noticed that in your recent work you are particularly talking about the “modern.” I would like to ask you what is it you are conscious of here.

Miura: Different people have spoken from many different positions about what has happened to the arts since the modern period. Just to limit us to thinking about Japanese theater, there was the period of Shingeki, when modern drama was imported from the West, and at the same time there were writers who were very self-conscious of the modernization of Japan. I have come to look at and pay more attention to these people. When I look at them I wonder, what did they think about imports from the West? How were they conscious of modernization? In the “NIPPON Bungaku Series” and “CHITEN no kingendai-go,” with Ryunosuke Akutagawa, Osamu Dazai, Yukio Mishima – well, I didn’t actually do Mishima – I am perhaps using the word “modern” a bit self-consciously, but I feel like I am being taught by these Japanese writers.

Dealing with texts on the issues surrounding postwar Japan, and after reading “Toka Tonton” by Osamu Dazai, written as if after listening to the Emperor’s Gyokuon-hoso radio broadcast announcing Japan’s surrender, I thought I have to learn more about the issue of the Emperor’s responsibility for the war, and that just treating it as if there was none is a bit too easy. Especially now I am living in Kyoto it makes me aware of the strange presence of Gosho [the Emperor’s residence in Kyoto], because no one is there, it’s a void. I can’t help but be aware of his absence, and also, connected to the earlier point about layers, in the case of Kyoto it was not so damaged, so the streets remain. Thinking about how Kyoto was not burned down in the war led me to think about the period of Japanese modernity.

Chiten, “Toka Tonto” (2012) at Kanagawa Arts Theatre. Photo by Tsukasa Aoki

Chiten, “Toka Tonto” (2012) at Kanagawa Arts Theatre. Photo by Tsukasa AokiHashimoto: Did using texts by these writers cause any actual changes during rehearsals?

Miura: Till now my work has been about using the filter of translation to look at how to articulate a foreign text into our Japanese, into our words. But using texts by Japanese writers means you do not need to translate. Yet the concrete work with these texts that don’t require translation turned out to be very tough. When citing work by Minoru Betsuyaku even just a little, I thought I understood his work simply because it was Japanese. Thinking you understand like that is dangerous. When staging Chekhov or Ibsen, I don’t understand the texts at all. And that’s the default. I try to understand the texts at an intellectual level by reading notes and even for dialogue that is emotional, there are parts that I do not understand to a certain extent. How to trace this – or not to trace it at all? This is my main work. For writers, you can be on a par with them. With Japanese writers, particularly someone like Osamu Dazai who is from Aomori, I know his context really well since my parents are from Akita. I kind of understand at the surface level and so my interpretation is lyrical. If it was Russia or Norway, I could maintain equidistance. But with Aomori, how am I to understand it in terms of how I work? When I tell the actors that this part will be lyrical, this part a yearning spirit, I then have to explain the reason too [laughs]. A characteristic of my recent rehearsals is that I have to give presentations to the actors.

What was interesting to me was that when we tried to read the text of the radio broadcast by the Showa Emperor in both the original text and a colloquial translation, well, to put it a bit strangely, there was nothing personal in it. There was no subjectivity at all. No matter which actor read it, it was the same. In particular, the Emperor’s radio broadcast is a text that stimulates lots of thoughts, like strict censorship. In this sense we don’t have to question the subjectivity of the text. It was a very interesting experience how we could just plunge straight into the content of the text itself. I could realize that there existed language without subjectivity. Of course, though, you are then tense when you do this since you have to think how the words will be received after you have verbalized them.

Working as a “Dot” Within the City

Hashimoto: I see. Whenever I think about a text without subjectivity, I always think of the words that appear on the Internet. We don’t exactly know who writes them and we can’t rigorously check if the information is correct or not. And through copy and pasting, these texts then are dotted about in all kinds of places far away from the writer. If I relate this to the idea of the city, there are many layers and different people in a city. Yukichi, your work has explored themes of migration, and I remember you saying once that the way of thinking about migration in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries are completely different in scale. Over the last decades the movement of information and people has become much more dynamic, resembling the structure of the Internet invented 20 years ago. And the movement itself of us in reality, more than thinking we have a center and surroundings somewhere, now is like a variety of things scattered around. This seems to happen not only in the online world but also the real city. I want to ask both of you who work not only in Kansai or Japan what do you think about this?

Miura: Yukichi, are you originally from Osaka?

Matsumoto: I am originally from Amakusa in Kumamoto, Kyushu. I moved to Osaka in the first grade of elementary school, when I was around 10 years old, so I have been in Osaka for 50 years. Like the theme for this year’s KYOTO EXPERIMENT, there is a map my body knows. I don’t need a map, my body remembers the map. And if your sense is good, you will always find a good place. To approach a city, especially a city like Osaka, requires you to have your own map inside your body. I somehow understood Kyoto as a city that gives you a panoramic view without having to walk around. Looking over the city from the Higashiyama mountains, you can see the Kyoto-esque townscape. This is in contrast with Osaka where everything is scattered around.

Hashimoto: Recently I was invited to be a part of a symposium with people from Osaka’s art and publishing fields. I was surprised to find with the people who came that in Osaka, which is more of a metropolitan than Kyoto, people in the same fields are very close. I raised this as a question to people there and I got some responses like, “On the contrary, Osaka is not a place where people can meet easily” They said, “Especially when it comes to art and culture, there is no center like a big theater where people can come together, so small gatherings are scattered around the city.” This was utterly different to my own singular, vague image of Osaka as a big metropolitan city.

Matsumoto: In this sense, Osaka’s geographical feature is easy to understand. In Osaka, each point west and east, south and north consists of different historical layers. People coming from different areas accidentally meet each other. They both probably feel far from each other in terms of time and distance, in their themes and eras. They don’t share a strong sense of concurrency, which makes me feel that we live in a big metropolitan city… And it is just at a time like this that I want to talk with feeling.

Hashimoto: Yes, if it is homogenized, all the things each and everything has will become dull. Only when this diversity is sustained is vitality then born.

Matsumoto: Yes, I agree.

Photo by OMOTE Nobutada

Photo by OMOTE NobutadaEncounters with Audiences at Overseas Performances

Hashimoto: By the way, Motoi staged his work abroad in the spring. How was it to encounter audiences with different cultural contexts?

Miura: I went to London, Moscow, and Saint Petersburg. Moscow was really good. You know the feeling when a performance goes well? In Moscow, our feelings were right on. While our cultural contexts were totally different, we staged classics in Moscow like Chekhov and Shakespeare, so they understood the content to some extent. It’s a strange thing to say but you can’t cut corners in Moscow, because the audience definitely sees through it. It was unusual for me to feel like I could pick up the reactions from audiences straightaway whether it was going well and badly.

Matsumoto: Is there anything in the Moscow theater scene that is similar to the Japanese theater? For example, the division between small independent fringe theaters and big, commercial ones?

Miura: There is no real distinction between commercial theaters and small fringe theaters. Everything seemed to me to be artistic and social, with no boundaries. Of course, after perestroika things seem to have drastically changed. This might not answer your question, but I noticed that even in the small theaters there are pictures of Putin and the theater manager, meaning the president came to the theater. What this means is that theater possesses a political nature. And, putting it another way, that theater is dangerous. There was a time when theater was dangerous and the traces of that somehow just about remains even now.

Matsumoto: The theater is rightly considered dangerous

Miura: Yes. And, this is a strange thing to say, but the audiences also probably just ordinarily come to see plays, like watching TV. That’s the first big difference.

Hashimoto: Does that mean there is proximity?

Miura: Proximity. And they also see lots. It’s odd to call them “professional” audiences, but they seem to see a lot and know the theater well. I don’t want to simplify things by just saying they are experienced, but seeing a play at a theater seems closely connected to the actual lives of the audiences. On the other hand, London was a different story. It was like staging something in Tokyo. There is this hospitality and a real vibe, but it seemed to me that theater fans and tourists go to the theater as a kind of status symbol. In Moscow, though, a person’s actual life and watching a play seemed surprisingly connected.

After returning to Kyoto, we put on a play in a small café with only 20 to 30 seats. Unless we little by little intentionally create proximity in this way, we will just move further away from our audience. At the café our efforts were low-key, like offering free drinks after the performance and chances to talk to the actors or to me. I wasn’t interested in this kind of thing in the past but I’ve started to do it. Lately, I make sure to show my face at the curtain call for each and every performance to really make it clear that I am the director, that it is I who is responsible for the play. The information could get confused at all kinds of points, so it’s like I want to take the heat right on the stage. I am conscious of different things now following my recent overseas performances.

Talking of Kyoto as a city, I think Kyoto needs a decent theater, a decent western-style theater. I think we need to experiment with this idea. As a city Kyoto has a perfect size and perfect intimacy, and it’s also a place that doesn’t get interfered with. We need to build a theater that audiences can trust for quality programming. For me, this kind of idea would connect to the physicality of Kyoto, or Kyoto as a city itself.

Hashimoto: It’s interesting that by going to various places you have been inspired to think about feelings of distance from audiences, and about the seating.

Miura: How about you? Can we succeed overseas?

Matsumoto: I think it’s difficult. Like Motoi, I also think that a director should put himself out there. When I am in Osaka, I can just drink, but when you’re overseas, you have to be in the lobby. Does this bother me? Actually, I kind of enjoy it. While a play is a play, that kind of exchange with audiences in a lobby can have more truth. Like their way of asking questions, not asking them in Japanese, these might guide what we are intrinsically thinking, make it essential. I enjoy these exchanges. That’s the reason why I actively seek out opportunities to stage production overseas. Obviously, it’s not that every city is interesting, that’s not possible. Well, those episodes about Moscow were very rich, though.

Miura: I think Moscow is the exception of the exception.

Matsumoto: No matter where you go, it’s normally only the elite who come to the theater. In this sense, Singapore where I went before was the most interesting place. Staging something outside is nice when it’s in a place that is not a theater.

Miura: The place where there is no status.

Matsumoto: Yes, there are no audiences that simply come “with” a theater, so many young people also go on their accord. Our performance was kind of about the outbreak of World War Two, and the theater was on the Malay Peninsular exactly where the Japanese military had landed.(*2) For this reason, our post-performance talk was really potent and interesting.

Ishinha, “When A Gray Taiwanese Cow Stretched” (Wandering With “Him”: The 20th Century Trilogy Part 3) (2011) Festival Village. Photo: Matthew G Johnson

Ishinha, “When A Gray Taiwanese Cow Stretched” (Wandering With “Him”: The 20th Century Trilogy Part 3) (2011) Festival Village. Photo: Matthew G Johnson

Hashimoto: There is a place where the seats arch over the stage. In this sense, the conditions in Japan are quite distant. Thinking about seating problems is the kind of issue I have to tackle as a theater producer as well. To get a hook on distant audiences, I end up asking artists just to move things closer to the seats. I don’t know if that’s the good idea because doing so robs the audience more and more of their own active engagement.

Miura: We are talking about a very difficult issue right now.

Matsumoto: Talking about audiences is bit difficult, but what I understand now is that the theater scenes in Kyoto and Osaka seem similar and yet completely differ. So, the Ishinha style is the best for Osaka [laughs]. Recently I could understand that having a center is impossible. In Kyoto, anywhere can be the center. Just a quick look and you can see that. In Osaka, large and mid-sized theaters have closed down, but many independent fringe ones are still alive, just like “dots.” I might never have been to them, might never have seen or heard anything about them – but they are open, they are alive. And this has become a situation that is fine. One day it might be over here that bursts open, another time perhaps over there, so it feels better just not to have a center. Wherever you do it, you cannot make a center, and on the contrary, in Kyoto, wherever you do it, anywhere can be a center. Well, this is just my intuition anyway!

*1 A series of stage adaptations of Japanese literary works made as co-productions with the Kanagawa Arts Theatre (KAAT). Productions until now have included “Kappa/Aru Shosetsu” (from the story by Ryunosuke Akutagawa) (2011) and “Toka Tonton” (adapted from the story by Osamu Dazai) (2012).

*2 “When A Gray Taiwanese Cow Stretched” (Wandering With “Him”: The 20th Century Trilogy Part 3) was performed as part of the Singapore Arts Festival 2011 at Esplanade Park.

■ date:30th August 2012(Thu.)■ place:Kyoto Art Center

Yukichi Matsumoto

Born in Amakusa, Kumamoto, in 1946. He formed Ishinha in 1970 and has garnered attention for unparalleled stage design, music using original irregular beats, and the unique rap-style “Jan-Jan Opera” he has created. His major work includes “Sakashima,” staged using an entire baseball ground, “Kokyukikai,” which caused a sensation for its “water stage” built at Lake Biwa, and “When A Gray Taiwanese Cow Stretched,” staged at an outdoor theater constructed from some 4,000 logs. Since 2011 he has been making the “Landscape” series, without extensive theaters or sets, but rather deeply engaging just the bodies of the performers with a landscape. He has been invited overseas numerous times, including to Oceania, Europe, and Central and South America. His work has won many awards, such as the Medal with Purple Ribbon in 2011.

Motoi Miura

Born in 1973, Miura graduated from the Department of Drama at the Toho Gakuen College of Drama and Music. In 1996 he joined the directing department of Seinendan Theater Company. After spending two years in Paris as a researcher for the Agency of Cultural Affairs, he returned to Japan in 2001 and devoted himself to the activities of his theater unit Chiten. In April 2005, Miura left Seinendan and moved his base to Kyoto. He has been re-creating the four masterpieces of Chekhov since 2007 and in the same year he won the Agency of Cultural Affairs New Director Award for his production of “The Cherry Orchard.” His work abroad is outstanding, including his invitation to direct at Shakespeare’s Globe in London in 2012. His writing includes the book “Is just being interesting OK?” In 2008 he received the Special Promotion for Arts and Culture Award from the City of Kyoto and in 2010, the Kyoto Prefecture Culture Award. At present, he is a visiting professor at the Department of Performing Arts at Kyoto University of Arts and Design.

Yusuke Hashimoto

Theater producer and head of Hashimoto Yusuke LLC. He began working in the theater in 1997 while at Kyoto University. In 2003, he founded Hashimoto Production Office. His work includes company production for contemporary theater and dance, and planning and producing for the “Engeki Keikaku” project at Kyoto Art Center. He has been program director for KYOTO EXPERIMENT since 2010.